The Buxton test

Buxton has said that the solution is to "stop focusing on the individual objects as islands". He has come up with a simple standard for whether a gadget should even exist: each new device should reduce the complexity of the system and increase the value of everything else in the ecosystem.

I've already briefly written about Wired's article on Disney and the design after screens. One of the highlights of the article was the interview with Bill Buxton. He proposes a two-pronged test for whether or not a device should be added to an ecosystem.

After reading the Wired article, I had some questions. I felt a little bit unclear about what Buxton meant by "value" and "complexity." I liked the idea of increasing the value of everything else in the system, but wasn't sure what type of value was being created. I was also confused by the mention of complexity. Surely adding a device to a system would increase the complexity of that system? To help answer these questions, I tracked down a recent talk that Buxton gave on Designing for Ubiquitous Computing (Slides for the talk).

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZQJIwjlaPCQ&w=560&h=315]

The entire talk is well worth watching (more than once), but I wanted to pull a few things out of the talk that helped answer the above questions.

The Three Miracles permalink

Buxton presents the idea of the three stages of technology. Each of the three stages is associated with a "miracle."

The first miracle is “It works!” He gives the example of the Altair. It was amazing that it worked. So amazing that people were willing to put up with the fact that the text editor crashed so often you had to save the buffer every 30 seconds.

The second miracle is “It flows!” This is the point at which things became easy to use. He gives the example as the first iPhone in 2007 as the tipping point. It was the same functionality, but the experience has changed.

The third miracle — “It works together” — hasn't quite happened yet. This is the point where you can't see the computer. Nothing intrudes on what you're doing. Buxton give the year this is likely to happen as 2015, so he thinks it's close.

The Cracker Jacks principle and complexity permalink

To explain what he means by complexity, Buxton cites the old slogan of Cracker Jack—“The More You Eat, The More You Want.”

Cracker Jack ad: "The More You Eat, The More You Want."

Cracker Jack ad: "The More You Eat, The More You Want."

The same thing is happening with the experiences we have with our devices. As we our devices become easier to use, we want more. The problem is, as you eat more Cracker Jacks, you get full and you hit a point where you are too full. Similarly, as our devices become less complex, the ecosystem into which they are added becomes more complex.

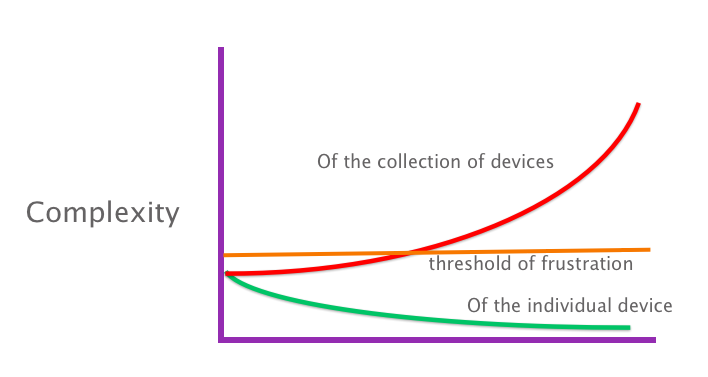

As our devices become simpler to use, using our collection of devices becomes more complex, crossing the threshold of frustration.

As our devices become simpler to use, using our collection of devices becomes more complex, crossing the threshold of frustration.

As the system becomes more complex, we become frustrated. Buxton posits that at some point this crosses a threshold of frustration, or “complexity barrier.”

The Buxton test permalink

And this brings us back to what I've been calling the “Buxton test.” Buxton himself doesn't call it this (and there is another, unrelated Buxton test). Nevertheless, I like the way it sounds.

The test has two rules.

- Every new product and service must provide great experience and excellent value—it works and if flows.

- But each must also reduce the complexity and increase the value of the others. Things work together.

The first rule refers back to the first two miracles. And the second rule refers to the third and future miracle.

As the oft-quoted William Gibson phrase has it, "The future is already here — it's just not very evenly distributed." To prove that point, Buxton gives the example of using a mobile phone in a car. When you're driving, you shouldn't be looking at the screen. The interaction is entirely based on voice recognition. If you're having a conversation while driving, park the car and get out, this changes. At that point, several transitions happen: from inside the car to outside; from driving to walking; from hands-free to holding the phone; from using voice recognition to the visual interface. If those transitions have been thought through and and designed well, nobody notices that they're happening.

No device is an island, or transitions over states permalink

As indicated in the first quote in this post, Buxton is encouraging us to stop thinking of devices on their own, and to start thinking about the wider ecosystem. This is what Eliel Saarinen would have called designing for the next larger context. To do that, we need to be thinking about these transitions.

These things here are transitions. They're not states. Remember I talked about "flow?" The flow now goes meta and it's not about the flow within the device, but the flow within the relationship and the changing social relationship among the devices. And this has to be done by design… And all of that presumes reduction of complexity, and not intrusion, so I can focus on my primary task.

This is like going from wireframes to prototypes, where we get a feeling for the transitions between screens. As Buxton says, "The feeling is way more important than the visuals." Just as the movement between screens is more important than the screens themselves, we need to consider each product or service in the next larger context:

In the future the quality of the experience will be determined how products work together, in concert, with the rest of the eco-system, not just by the quality of any product on its own—no matter how good that individual experience is.

And that brings us all the way back to my questions of what Buxton meant by “value.”

That is the challenge of the future growth and the future value. To actually let us get on with our lives, and the quality of life and the quality of experience in our business life and hour home life and our educational life.

This seems to align well with the idea of creating more value than you capture. We can create that value by getting out of people's way and by facilitating what they need to do, rather than intruding on their lives.

The society of appliances permalink

For me, the most exciting point of the talk comes around 45 minutes in, when Buxton discusses the “society of appliances.”

It's not just about the hardware; it's not just about the software... It also involves redesigning the business models; and redesigning the partners; and redesigning not just the relationships amongst the devices, but renegotiating and rethinking who are your partners and what are your relationships in terms of business. And as we move into the society of appliances, it's not a technological play, it's a social, cultural play. Who are you partners? How do you work? How do you work together? How do you join? Because the society of appliances live within the society of people.

This made me think of Bruce Nussbaum's point about the difference between innovation and invention. An invention is of no real use to most people until it has a socio-economic value. Doing that is the hard part. The creation of value is possibly even more important than the reduction of complexity, though the two are intimately related.